Growing up on the periphery of the jewish community in Montreal in the `80s, I was aware of Leonard Cohen’s presence from an early age. I remember my 10 year old self watching a 30 year old Leonard Cohen in the 1965 documentary Ladies and Gentlemen...Mr. Leonard Cohen1. It was on CBC past my bedtime, but it was in black and white, and it was about Leonard Cohen, so I watched it. My only clear memory of it was that he was naked in his bathtub at one point. He appeared to me as an alien being probed by the filmmaker. Watching it again now, my reaction to seeing young Leonard is primarily one of cringe. What is this feeling? What unexamined beliefs piggyback its appearance? I repeatedly pause the flick and dive into the queasy experience.

Of course the 10 year old me didn’t cringe. Mostly I hadn’t understood what I was watching at all, but I was in awe that someone could be naked before others. I don’t just mean without clothes. Even back then I recognized that he was absolutely dedicated to… something that took precedence over concerns of appearance. Was it authenticity? And why do I cringe now? Is it his otherness, or do I recognize something in him that I can’t tolerate being aware of in myself? Is it his humanity, when I demand to see a god? If I choose to dedicate myself to truth and transparency, how far might I go? If I can’t even bear to look at someone I claim to admire, how can I hope to look at myself? And how can I discover who I am – and what I’m capable of – unless I allow myself to follow my nose whilst simultaneously consuming my own wacky reflection, as Leonard seemed to be demonstrating.

Though dedicated to authenticity, Leonard sprinkles some clues throughout the film that all is not as it appears. He questions his own ability to actually be transparent in the context of a watching camera. The act of intentional transparency itself quickly begins to look like a ridiculous pretence, and he acknowledges this. He doesn’t want to pretend, but he admits that this is exactly what’s happening.

I think the same thing that attracted me to young Leonard is also what resulted in my cringe reaction. It was his unabashed earnestness. It was the way he took himself so seriously. Growing up engulfed by the songs of his 1967 debut album, I too took him seriously. Suzanne had me mesmerized. I had the sense that, one day, I would understand this song, and then I would finally understand life. (It’s taking longer than anticipated. While my children were still young enough, I would sing Suzanne to them at bedtime. It still seemed new, and I would regularly imagine new connections to my then current experience.)

Leonard was also trying hard to understand. He tried many things. He tried Kabalah, and Jesus, Buddhism and the I Ching, psychoanalysis and Scientology, LSD and Prozac, indulgence and renunciation, to name but a few . Leonard was in spiritual pain. He sounds desperate and as if on the brink of giving up altogether on his 1971 album where he sings that most exquisite expression of raging nihilism, Diamonds In The Mine. That song (along with the later Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On) pairs too well with the 1972 footage2 of Leonard in Berlin when he leaves the stage, goes off into the crowd and finds himself writhing around on the ground with a young woman he just met. The shot from the documentary leaves to the imagination what actually happened, but later he utters to the filmmaker, “I disgraced myself, I have.”3

Perhaps Leonard was conflating authenticity with self-indulgence. It’s a common confusion. Still, he is intent on being exactly where he is and refuses to knowingly pretend. In his first concert in Israel, in 1972, he has to walk off the stage in tears after telling the audience:

Now look, if it doesn’t get any better, we’ll just end the concert and I’ll refund your money, because I really feel that we’re cheating you tonight. You know, some nights, one is raised off the ground, and some nights, you just can’t get off the ground. And there’s no point in lying about it. And tonight, we just haven’t been getting off the ground. It says in the Kabbalah… that if you can’t get off the ground, you should stay on the ground. No, it says in the Kabbalah that unless Adam and Eve face each other, God does not sit on his throne. And somehow, the male and female part of me refuse to encounter one another tonight, and God does not sit on his throne. And this is a terrible thing to happen in Jerusalem.

Backstage, he and his band end up dropping acid before getting back on their feet and killing for the rest of the night.4

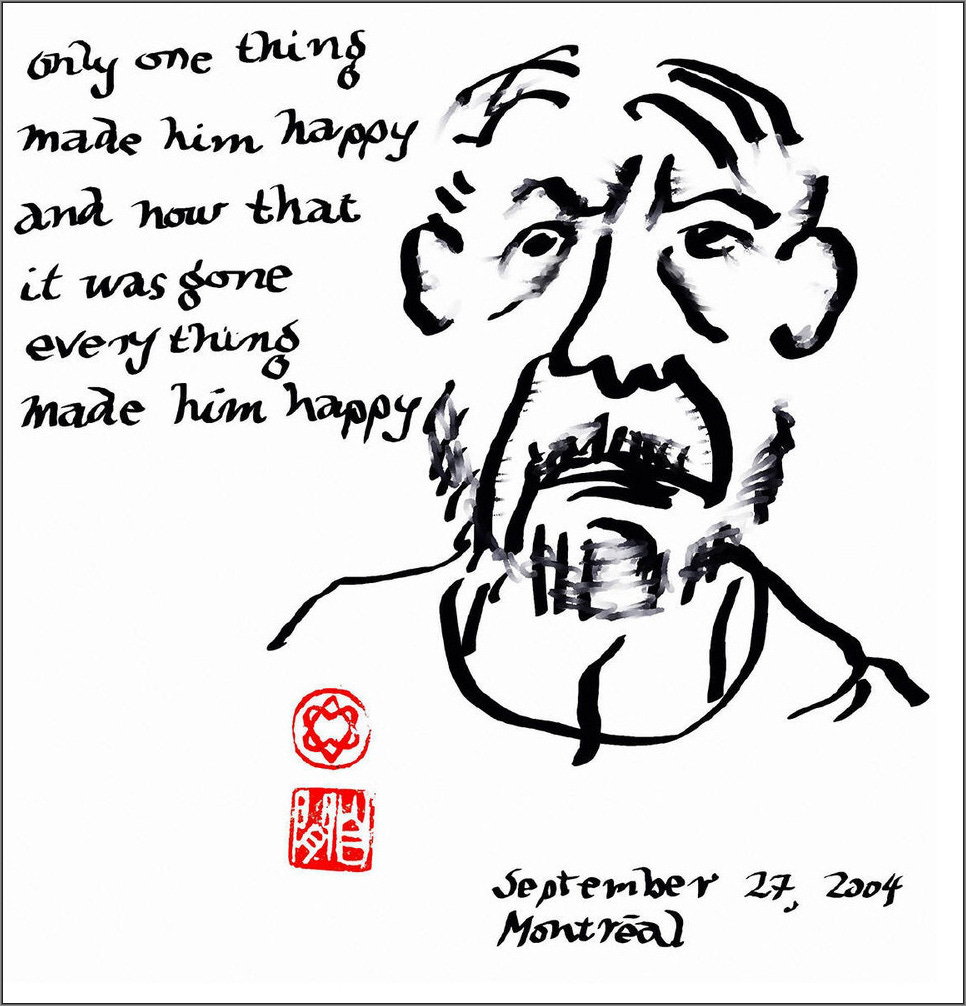

Leonard struggled with ups and downs5; from visions of a higher purpose, to a chilly bleakness that hit me in 1992’s The Future. (The Future was one of two album purchases that my 15 year old self made that year. The other was Tori Amos’s Little Earthquakes. Three years later she did a great version of Famous Blue Raincoat). However, at some point his view of the continuing emotional and spiritual tug-of-war seems to have become totally clarified. Listen:

O Crown of Light, O Darkened One,

I never thought we’d meet.

You kiss my lips, and then it’s done:

I’m back on Boogie Street.…

And O my love, I still recall

The pleasures that we knew;

The rivers and the waterfall,

Wherein I bathed with you.Bewildered by your beauty there,

I’d kneel to dry your feet.

By such instructions you prepare

A man for Boogie Street.

Excerpt from Boogie Street (2001)

And what is Boogie street? Leonard mostly tells us what it’s not. It’s not the depression of oblivion, but neither is it the delirious high of some glimpsed eternal meaning. When he says, “I'm wanted at the traffic-jam; They're saving me a seat,” we understand that Boogie street is there whether or not he’s cognizant of it. Boogie street, the ground to a halt traffic-jam, is the most ordinary of mundanities: a forgettable in-between space — between moments and out of time — from which we habitually flee as soon as practical. Ever-pregnant, it is the source from which all fleeting kisses simply spring forth and then finally return to. In this way of seeing, everything in our life that appears as meaningful, or else meaningless is, all the same, something of ritual: appearances become self-secret symbols, serving only as a gateway into direct and immediate experience of the here and now, without providing support for any fixed certainties of any one thing or another.

Leonard battled with depression throughout most of his life, but 2012’s album Old Ideas (older than Leonard6) finds him, at least at moments, seemingly happy and downright amused by himself. Listen to Going Home. He calls himself a “lazy bastard living in a suit”, but what comes through his voice is the gentleness and joy at the declaration. In addition, Leonard is admitting that there is an eccentricity that is driving him now:

He wants to write a love song

An anthem of forgiving

A manual for living

with defeat

A cry above the suffering

A sacrifice recovering

But that isn’t what I need him

to complete

I want to make him certain

That he doesn’t have a burden

That he doesn’t need a vision

That he only has permission

To do my instant bidding

Which is to say what I have told him

To repeat

Except from Going Home (2012)

For years Leonard has written poetry as his way of coping with depression7. Many artists live here, and many even believe that their suffering is part and parcel of the creative act. In this way a cycle of self-indulgence and self-immolation fuels the confusion that the work pretends to finally clarify, but instead simply restarts. Perhaps the pain and the writing were the most consistent elements that followed Leonard throughout his years. Here though, he turns the whole enterprise on its head. He says that he won’t write at all, unless he knows for certain that he’s fundamentally ok beforehand. He won’t write until he knows for sure that there is nothing that needs to be done in order to heal himself; that there is, in fact, nothing in need of healing.

I think about my own motivations in writing this essay. I’m not a writer, even as I pretend to play one on the Internet, but I do enjoy writing. Still, I recognize: Beneath the joy of creative expression there lurks the desire to prove something: no matter if to myself or to others. Will this act serve somehow as an attempt to prove my self-worth? For, if yes, then I should understand clearly: Such validation is temporary at best. Inasmuch as it validates anything whatsoever, it won’t sustain for more than a bit, and then I’ll be on to the next fix. In this way the act of creation will actually reinforce the semi-conscious belief that I will not be whole until some imagined future fruition… again and again. Perhaps making art or being productive or gaining insight into the historical and psychological basis for one’s current patterns is a healthier way of coping with existential angst than, say, taking recreational drugs, scrolling one’s social media feed, or fantasizing about a possible purchase. Nevertheless, in some ways they all share a common deficiency. Leonard is no longer interested in that kind of contingent relief from the pain of existence. Instead he homes in on a freedom that is always, and only ever available as the groundless experience of right here and right now, regardless of happiness, sadness, personal preference, clarity, or confusion. That type of freedom can’t be validated; nor can it be invalidated.

Though there is a logic to his thinking, ultimately Leonard admits that reason is secondary in imposing on himself the prerequisite of “no burden.” He sees his choice as primarily aesthetic, and makes no appeal to artistic integrity, morality, philosophy, religion, belief or anything of the like. Listen as he argues with himself about whether or not he should continue to write the poem he’s in the midst of composing, or perhaps whether or not he should even continue to write poetry at all:

You want to live where the suffering is

I want to get out of town

C’mon baby give me a kiss

Stop writing everything down

Both of us say there are laws to obey

But frankly I don’t like your tone

You want to change the way I make love

I want to leave it alone

Except from Different Sides (2012)

In 2014’s Slow, Leonard declares, “slow is in my blood.” I too have “always liked it slow,“ which is perhaps one of the reasons that Leonard’s aesthetic grabbed me from an early age. What I can’t much relate to though, is the steady diligence he applies to his craft. Leonard famously spent five years writing Hallelujah, composing more than 100 draft verses8 before finally calling it good enough. This is my first essay that’s taking me more than one sitting to complete, and after a handful of one-night stands, I’m ready to explode. Aside from having to endure the anxious, twisting experience of impatient desire, I’m also forced to re-read my own writing repeatedly. That shit is cringe-worthy! Why this feeling again!? Maybe it’s seeing myself pretending or even just trying. Maybe it’s the same cringe that I experience when watching young Leonard. Then again, maybe it’s a drop straight to Boogie street.

It’s not as though Leonard claims to be unaffected by the opinions of others (or himself). Listen to Almost like the blues:

I have to die a little

Between each murderous thought

And when I'm finished thinking

I have to die a lot

There's torture and there's killing

And there's all my bad reviews

The war, the children missing

Lord, it's almost like the blues

So I let my heart get frozen

To keep away the rot

My father said I'm chosen

My mother said I'm not

I listened to their story

Of the Gypsies and the Jews

It was good, it wasn't boring

It was almost like the blues

Except from Almost like the blues (2014)

Filing his experience of bad reviews into the same folder that houses missing children and nazi genocide, we discover Leonard viewing history and psychology, the world outside and the world inside, as but one. He hasn’t overcome negative affect: he seems as plagued as ever. However, he now sees it all together, noticing a peculiar type of beauty to the tragedy that is inextricably bound with living in the world. Leonard sees that his historic reaction to such experience of pain was to “let my heart get frozen;” he says, “I was staring at my shoes.” Our reflexive attempts at self-protection typically take the form of either looking away, or else acting out our anger, frustration, whatever. Finally though, the “invitation” to an alternative to these habitual modes presents itself, “and it's almost like salvation; it's almost like the blues.”

You Want It Darker, released 17 days before9 Cohen's death in 2016, finds Leonard looking back, as he looks around, finding the division between himself and everything else blurred beyond recognition. Listen to Traveling Light:

I'm traveling light, it's au revoir

My once so bright, my fallen star

I'm running late, they'll close the bar

I used to play one mean guitar

I guess I'm just somebody who

Has given up on the me and you

I'm not alone, I've met a few

Traveling light, like we used to do

Except from Traveling Light (2016)

In his later years, Leonard would sometimes repeat the words of his Zen teacher who told him, “You are not a Jew, I am not a Buddhist.”10 Eventually he seems to let go of any conception of fixed identity whatever, and laments past constrictive viewing, as when he says, “I'm so sorry for that ghost I made you be” in Treaty. If there were ever any words in Leonard’s writing that were directed at anyone other than himself, those days are long gone. As he begs in Leaving the Table, “You don't need to surrender; I'm not taking aim.”

At the end of the 1964 documentary, we watch Leonard view a screening of himself with the filmmakers:

Leonard [watching himself in bed]: It’s a very privileged thing to be able to see yourself sleeping…. Of course the fraud is that I’m not really sleeping.

Filmmaker: It’s a very privileged thing to see yourself pretending to sleep.

Leonard: Yes… that’s a privilege of a higher and more esoteric order. Because there are some people who are very interested to know how they look when they’re pretending…

I think I had a whole misconception about what style of man I was. And I think the whole thing is changing now.

Filmmaker: You mean just looking at this movie?

Leonard: Yea.

Filmmaker: That may affect your whole life.

Leonard: I hope it affects my whole life.

Leonard began his journey with hopes of overcoming his pain; of transcending himself. As a child, I found in him a symbol for all that I imagined I was not; I wondered wordlessly at his otherness. Today I wonder wordlessly at my own otherness, which I continue discovering as I re-read my own thoughts; as I begin to watch myself alternating between pretending and not pretending.

Perhaps we can, or perhaps we can’t overcome some of our historic limitations, but as a continuing goal it risks dangling the carrot of actualization forever out of reach. Maybe all the usual preferences, habits, dissonance and cringe factors will still be there in the end anyway. Maybe everything will remain the same. Then again, maybe something will be different. In any case, we can’t help but continue our journey in every waking moment, and “even though the news is bad,” we might occasionally and inexplicably find ourselves effortlessly falling forward with clarity, awareness, and compassion; without any ground to break our natural momentum. With only the subtlest possible of attitude adjustments, we might recognize the self-aggression and folly in the hope to escape our very personal human condition, but nevertheless begin to consider the possibility that even that kernel of fantastical desire is but another instant portal back to Boogie street.

So come, my friends, be not afraid.

We are so lightly here.

It is in love that we are made;

In love we disappear.Though all the maps of blood and flesh

Are posted on the door,

There’s no one who has told us yet

What Boogie Street is for.

Soundtrack

Suzanne (yt)

Diamonds In The Mine (yt)

Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On (yt)

Boogie Street (yt)

Going Home (yt)

Different Sides (yt)

Slow (yt)

Almost like the blues (yt)

Traveling Light (yt)

Treaty (yt)

Leaving the Table (yt)

Footnotes

Ladies and Gentlemen...Mr. Leonard Cohen (1964 documentary)

https://www.nfb.ca/film/ladies_and_gentlemen_mr_leonard_cohen/

Bird on a Wire (1972 documentary following Leonard on tour)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonard_Cohen:_Bird_on_a_Wire

I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen

https://www.amazon.ca/Im-Your-Man-Leonard-Cohen/dp/0771080417/

https://www.israellycool.com/2016/11/11/when-leonard-cohen-walked-off-stage-in-jerusalem/

https://bordercrossingsmag.com/article/leonard-cohen

See, for example, the Heart Sutra and corresponding experiential traditions that explore the non-duality of form and emptiness: https://www.evolvingground.org/

I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen

https://www.amazon.ca/Im-Your-Man-Leonard-Cohen/dp/0771080417/

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song (2022 documentary)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hallelujah:_Leonard_Cohen,_A_Journey,_A_Song

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You_Want_It_Darker

https://catholicherald.co.uk/so-long-leonard-thank-you-for-helping-me-to-find-god/

Love this essay ❤️